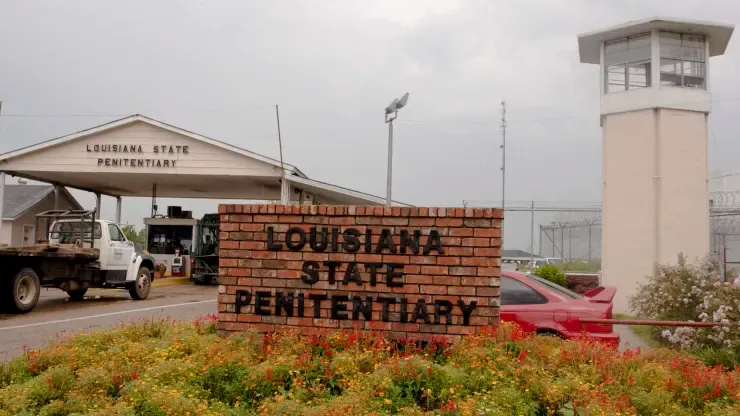

(CNBC) A hidden path to America’s dinner tables begins here, at an unlikely source – a former Southern slave plantation that is now the country’s largest maximum-security prison.

Unmarked trucks packed with prison-raised cattle roll out of the Louisiana State Penitentiary, where men are sentenced to hard labor and forced to work, for pennies an hour or sometimes nothing at all. After rumbling down a country road to an auction house, the cows are bought by a local rancher and then followed by The Associated Press another 600 miles to a Texas slaughterhouse that feeds into the supply chains of giants like McDonald’s, Walmart and Cargill.

Intricate, invisible webs, just like this one, link some of the world’s largest food companies and most popular brands to jobs performed by U.S. prisoners nationwide, according to a sweeping two-year AP investigation into prison labor that tied hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of agricultural products to goods sold on the open market.

They are among America’s most vulnerable laborers. If they refuse to work, some can jeopardize their chances of parole or face punishment like being sent to solitary confinement. They also are often excluded from protections guaranteed to almost all other full-time workers, even when they are seriously injured or killed on the job.

The goods these prisoners produce wind up in the supply chains of a dizzying array of products found in most American kitchens, from Frosted Flakes cereal and Ball Park hot dogs to Gold Medal flour, Coca-Colaand Riceland rice. They are on the shelves of virtually every supermarket in the country, including Kroger, Target, Aldi and Whole Foods. And some goods are exported, including to countries that have had products blocked from entering the U.S. for using forced or prison labor.

Many of the companies buying directly from prisons are violating their own policies against the use of such labor. But it’s completely legal, dating back largely to the need for labor to help rebuild the South’s shattered economy after the Civil War. Enshrined in the Constitution by the 13th Amendment, slavery and involuntary servitude are banned – except as punishment for a crime.

That clause is currently being challenged on the federal level, and efforts to remove similar language from state constitutions are expected to reach the ballot in about a dozen states this year.

Some prisoners work on the same plantation soil where slaves harvested cotton, tobacco and sugarcane more than 150 years ago, with some present-day images looking eerily similar to the past. In Louisiana, which has one of the country’s highest incarceration rates, men working on the “farm line” still stoop over crops stretching far into the distance.

Willie Ingram picked everything from cotton to okra during his 51 years in the state penitentiary, better known as Angola.

During his time in the fields, he was overseen by armed guards on horseback and recalled seeing men, working with little or no water, passing out in triple-digit heat. Some days, he said, workers would throw their tools in the air to protest, despite knowing the potential consequences.

“They’d come, maybe four in the truck, shields over their face, billy clubs, and they’d beat you right there in the field. They beat you, handcuff you and beat you again,” said Ingram, who received a life sentence after pleading guilty to a crime he said he didn’t commit. He was told he would serve 10 ½ years and avoid a possible death penalty, but it wasn’t until 2021 that a sympathetic judge finally released him. He was 73.

The number of people behind bars in the United States started to soar in the 1970s just as Ingram entered the system, disproportionately hitting people of color. Now, with about 2 million people locked up, U.S. prison labor from all sectors has morphed into a multibillion-dollar empire, extending far beyond the classic images of prisoners stamping license plates, working on road crews or battling wildfires.

Though almost every state has some kind of farming program, agriculture represents only a small fraction of the overall prison workforce. Still, an analysis of data amassed by the AP from correctional facilities nationwide traced nearly $200 million worth of sales of farmed goods and livestock to businesses over the past six years – a conservative figure that does not include tens of millions more in sales to state and government entities. Much of the data provided was incomplete, though it was clear that the biggest revenues came from sprawling operations in the South and leasing out prisoners to companies.

Corrections officials and other proponents note that not all work is forced and that prison jobs save taxpayers money. For example, in some cases, the food produced is served in prison kitchens or donated to those in need outside. They also say workers are learning skills that can be used when they’re released and given a sense of purpose, which could help ward off repeat offenses. In some places, it allows prisoners to also shave time off their sentences. And the jobs provide a way to repay a debt to society, they say.

While most critics don’t believe all jobs should be eliminated, they say incarcerated people should be paid fairly, treated humanely and that all work should be voluntary. Some note that even when people get specialized training, like firefighting, their criminal records can make it almost impossible to get hired on the outside.

“They are largely uncompensated, they are being forced to work, and it’s unsafe. They also aren’t learning skills that will help them when they are released,” said law professor Andrea Armstrong, an expert on prison labor at Loyola University New Orleans. “It raises the question of why we are still forcing people to work in the fields.”

A shadow workforce with few protections

In addition to tapping a cheap, reliable workforce, companies sometimes get tax credits and other financial incentives. Incarcerated workers also typically aren’t covered by the most basic protections, including workers’ compensation and federal safety standards. In many cases, they cannot file official complaints about poor working conditions.

These prisoners often work in industries with severe labor shortages, doing some of the country’s dirtiest and most dangerous jobs.

The AP sifted through thousands of pages of documents and spoke to more than 80 current or formerly incarcerated people, including men and women convicted of crimes that ranged from murder to shoplifting, writing bad checks, theft or other illegal acts linked to drug use. Some were given long sentences for nonviolent offenses because they had previous convictions, while others were released after proving their innocence.