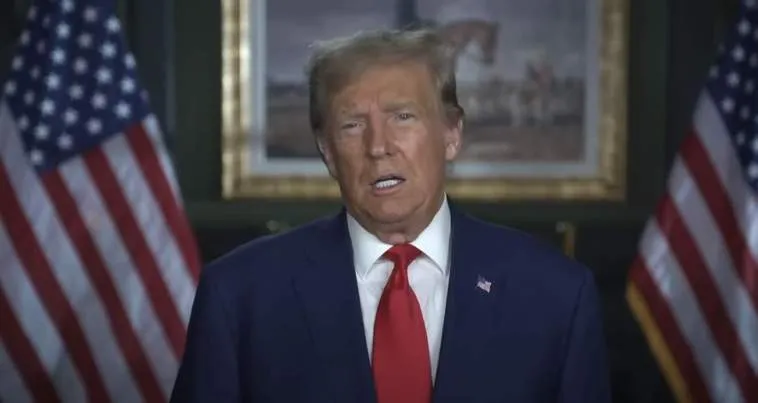

Below is my column in USA Today on the growing excitement among pundits on the prospect that former President Donald Trump could be going to jail. The celebration is a tad premature. Indeed, Trump could be convicted before the election and not be sent to prison for years, if ever. The prospect of prison depends on the specific conviction, long appellate challenges, and pardons.

(Jonathan Turley) With the indictment of Donald Trump, there is a palpable sense among many on the left that surely these indictments will bring about the long-desired incarceration of the former president. For some pundits and politicians, it is an anticipation that borders on obsession.

The Georgia indictment is a serious threat for Trump as is the Florida case. However, multiplying the indictments does not necessarily increase the chances of imprisonment before the election, or even during a second Trump term. However, the Georgia case does present a clear context for considering the prospect of prison for Trump.

The sense of anticipation was captured Monday on MSNBC, where Rachel Maddow and Hillary Clinton were shown laughing joyfully on the night of the Georgia indictment. The left is experiencing their own version of chanting “Lock him up,” with a boom business for merchandise celebrating the expected incarceration.

Yet, there is still a great deal of runway between the arraignments and any incarceration.

Let’s quickly review the four cases against Trump. The New York indictment, led by Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg, is the weakest. It is based on a thin legal theory pushed by a prosecutor determined to charge Trump for something … anything.

The first federal indictment is the strongest of the four. The charges over the mishandling of classified documents are based on established law and firm evidence.

The second federal indictment is similar to the Georgia case in terms of the underlying acts. Both the Georgia case and the federal indictment surrounding the Jan. 6, 2021 riot at the U.S. Capitol are based on the view that Trump and his associates knew that there was no reasonable basis to challenge the 2020 election.

However, Georgia adds state charges that could not only be difficult to challenge before trial but also are not subject to a federal pardon. The 98-page indictment contains 13 counts against Trump. The state charges include mandatory minimum sentences of five years in prison, with no leeway for the sentencing judge. Even five years in prison for a man who is 77 years old (and who never has been previously incarcerated) could be a terminal sentence.

As a threshold matter, a quick resolution of the Georgia case or the others is unlikely. Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis’ demand to try all 19 defendants together in six months is wildly unrealistic.

Given the competing criminal and civil proceedings previously scheduled around the country, the Georgia trial may have to wait until after next year’s election. There are also likely to be motions to remove the entire case to federal court.

Even if it were held in the midst of the election, a conviction would not bar Trump from appearing on the ballot or taking the oath of office on Jan. 20, 2025.

During the pendency of these prosecutions, Trump can continue to run for office. Indeed, even a conviction would not prevent him from running for president or serving if elected.

There is even precedent for running for the presidency from prison. That distinction belongs to socialist Eugene Debs, who was on the ballot in 1920 while he served time in federal prison.

If Trump is convicted, most courts would allow him to remain free pending appeals on the weighty constitutional and evidentiary issues raised by the Georgia case. That process could easily take a couple of years.

And if Trump were to win in 2024 and a judge were to order his incarceration during his presidency, there would be an immediate challenge. While state offenses are not subject to the federal pardon authority, Trump’s counsel (and likely the Justice Department) would argue that incarcerating a sitting president conflicts with carrying out his federal duties.

Even if Trump were to be sent to prison, he would not likely be thrown into general pop with a bar of soap and a weekly call. He currently has a federal security detail and, if elected, he would have presidential duties to perform. The state may have to yield to federal authority in how Trump is held to allow him to carry out his duties and to accommodate his security detail.

That challenge would take time, and the federal courts could balance the state and federal interests by delaying any incarceration until after the term. The courts also could effectively achieve that same result by extending the appellate process past the end of a second term.