(Reclaim The Net) Esports and competitive gaming inherit a lot from traditional sports, and one of those things is a tactic of undermining the opponent’s morale with “trash talking.”

But however significant and long-present, this practice, at least in esports, could be facing extinction at the hands of overzealous video game moderation tools.

What modern tools such as those used by big platforms like Microsoft are trying to “tackle” is by no means a new phenomenon, but as more and more people play against friends online, and the games in general are transitioning there, things like trash talking the opponent are increasingly on the radar of the ever-moving censorship targets.

What was once a mainstay of college dorm rooms in the 2000’s could soon be relegated to history as gaming, like pretty much everything else, gets filtered through the language censorship filters approved by Big Tech.

Before there was even computer gaming such as we know it, and esports in particular, there were traditional sports, where exaggerated claims and language have been used to gain sometimes more and sometimes less obvious mental advantage by preparing the ground of the actual game/sports clash by, more or less subtly, downplaying the qualities of those on the other side.

“Unsportsmanlike” it might have been seen by some, but it’s always been perfectly legitimate, not to mention legal. And effective. Just look at press conferences (until that gets outlawed as well) by any football coach, worth their salt, given in Europe and beyond.

And in some cases, successfully “trash talking” the opponent is considered a skill in its own right. All is fair in love and sports, it would seem.

Those who started playing computer games in the 1990’s and early 2000’s grew up as gamers in a very different environment. Once the multiplayer mode advanced, so did naturally the need to use more intricate means to advance your own chances and damage those of people on the other side. For that reason, trash talk came to gaming as naturally as the games themselves.

And that was only encouraged by esports – like traditional sports – moved from amateur, hobby-like passing of time, to professional levels where a lot of money is at play.

Esports competitors became bona fide professionals, and as such, they pursued every chance that might enhance their opportunity to succeed.

A Call of Duty player known as Joshh (Joshua-lee Sheppard) once suggested that trash talking was a huge part of esports – he assessed that it could sometimes play up to 40% difference between winning and losing.

In other words, like any other sports, games are all too often won and lost in the head, at the mental level, regardless of the participants’ preparedness and talent.

Esports pros realized that early on and a clear example of this “discipline” catching on and including trash talking into the gaming routine was evident some 20 years ago, specifically in the Halo community.

To be clear – this is not something any “moderator” (aka censor) should have, then or now, be worried about. One phrase that demonstrates how the early “game behind the game” worked is a Halo star David “Walshey” Walsh describing a victory over a particularly touchy opponent – a former team member – as reminiscent of “taking candy from a baby.”

And the practice was pronounced in those genres where you would expect it to be: games like Mortal Kombat, etc. Heaping mental pressure on the “enemy,” getting in their head – it’s basically a part of any sport, e- or otherwise.

But then started another kind of talk, that many critics will no doubt consider to be proper trash talk in its own right – that this was something tantamount to cyberbullying – and therefore, eligible for moderation, aka, censorship.

Some examples (in a sea of others that are not) of ad hominem attacks are cited as the beginning of this, such as a CS:GO pro asking another – as their interchange became more heated as the competition progressed – “I don’t think you have real life friends, do you?”

Not a nice thing to ask anybody – but, does it qualify as cyberbullying?

Those who said “yes” decided to interpret this jab as “going into someone’s personal life.” (How they knew what the personal life of the player on the receiving end was, or was not, in another matter).

Either way, trash talking started to be another potential cause for the woke crowd to fight against, using a myriad of interpretations, and inevitably, heralding and bringing in censorship into the mix.

It didn’t help that by this time, esports became big business, dependent on sponsors and advertisers, forever leery of any hint of real or imagined impropriety and insufficiently PC-behavior, particularly the kind that might incense the social media crowds. Once franchises get formed around an activity, you can inevitably expect that the level of corporate culture affecting the field, whatever it is, will only grow exponentially.

But, human nature, natural behavior under certain high pressure circumstances and, in particular, in a competitive environment like esports is bound to produce outliers.

Several years ago, the focus was on Riot Games’ VALORANT. The FPS players back in 2020 showed from the get-go that they would not throw away the good old trash talking tactic. It was good for the team, it was good for the game.

There have been other examples making it through the fire as far as the emerging cowering new world of online speech is concerned, where corporations all to often present disproportionate, fearful, knee-jerk reactions to what they think social and transitional media will criticize (and not seldom, criticize to death – driving individuals and companies out of business – and their minds).

Even as recently as three years ago, this has still not stopped those competing in 100 Thieves and Sentinels from engaging in some trash talking – even though reports said they were now involved in more “indirect” ways of getting under each other’s skin, on platforms like Twitter.

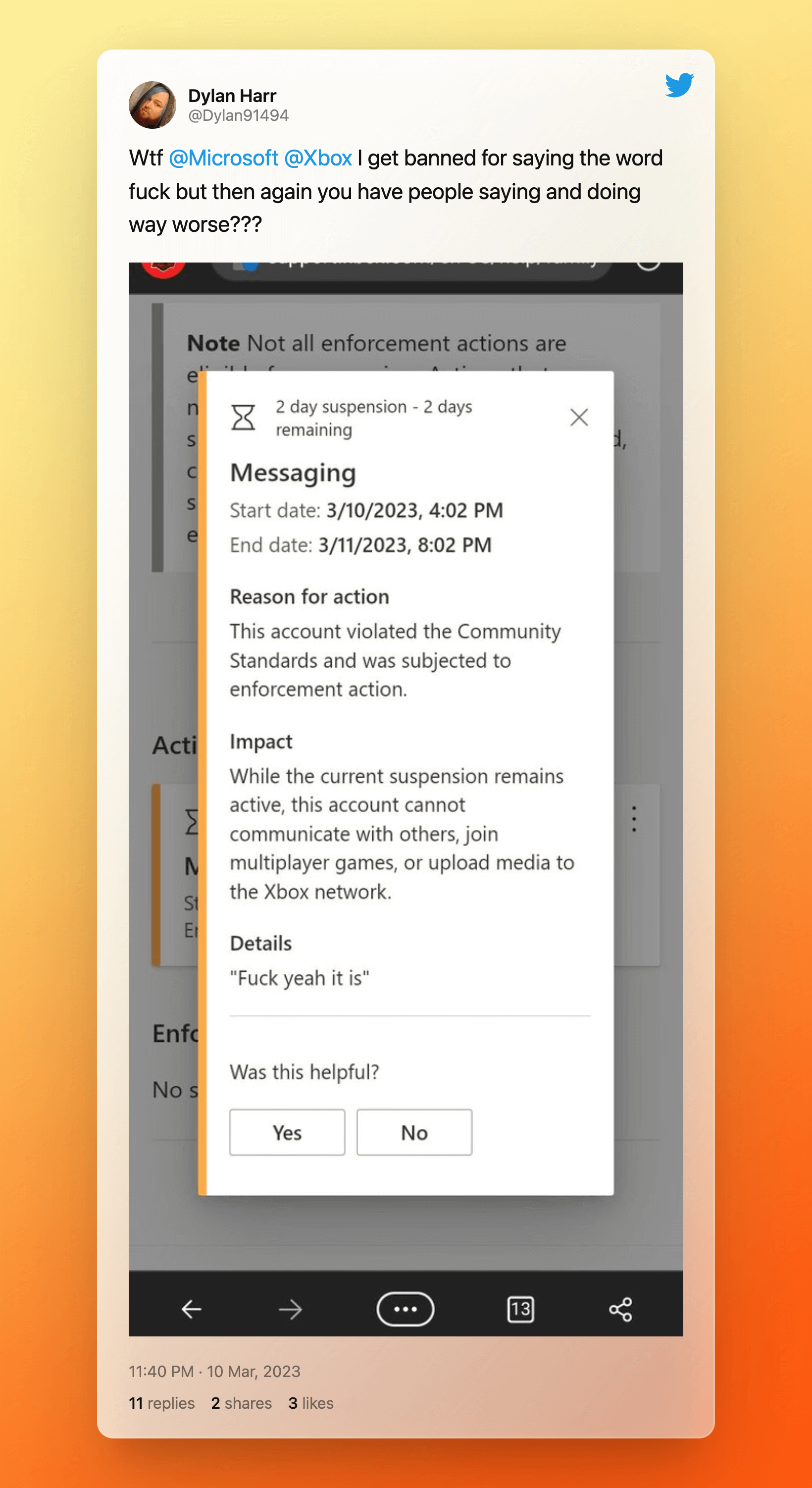

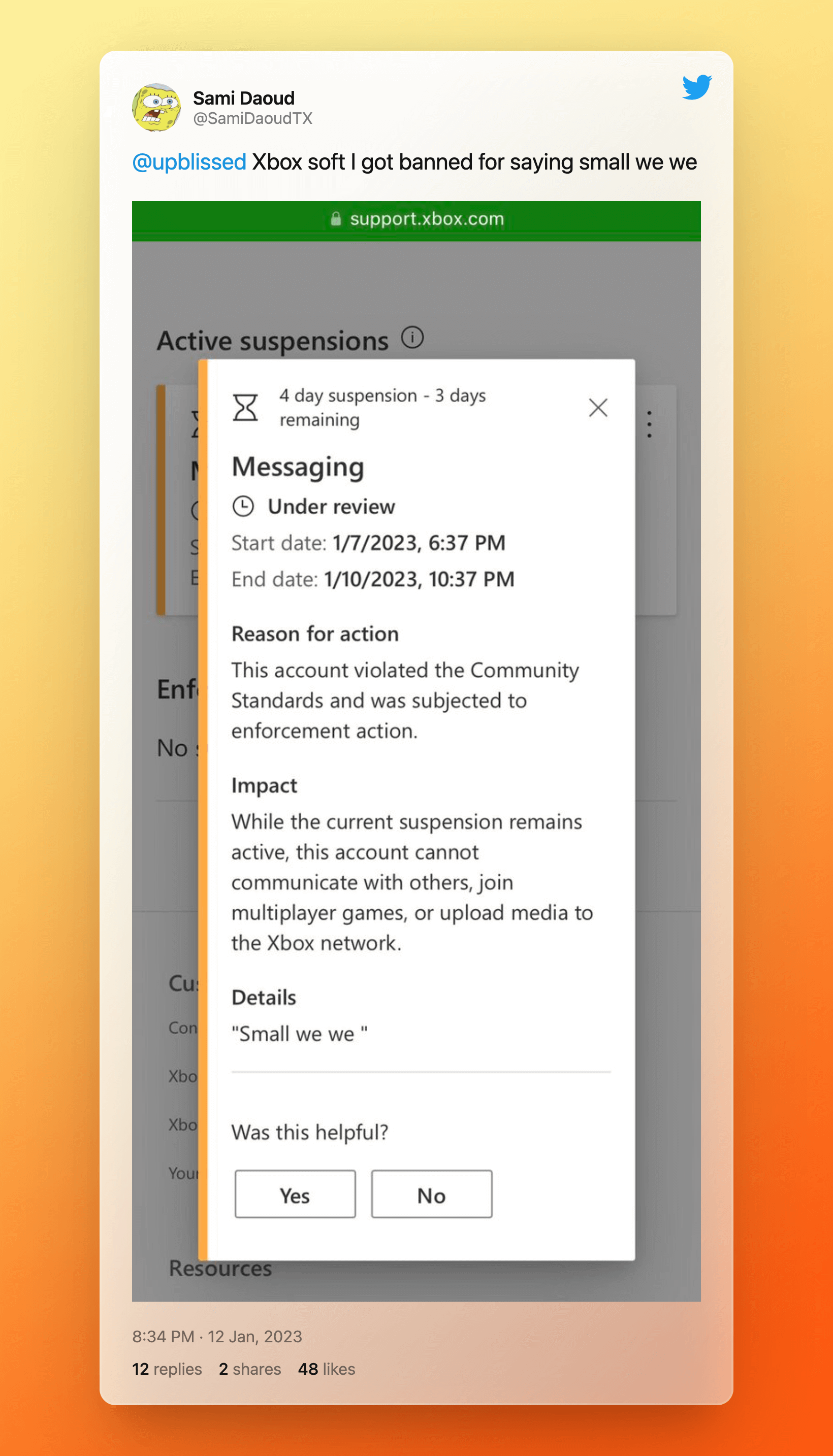

The term “toxicity” is now being thrown around a lot in this context. Trust the “people’s advocate,” – the notorious Big Tech giant Microsoft, that built its empire on improprieties of all sorts – such as antitrust behavior documented in numerous court cases – to position itself as a “savior” from what they decide is hate speech.

In May of last year, Microsoft came up with a paper called, “ToxiGen: A Large-Scale Machine-Generated Dataset for Adversarial and Implicit Hate Speech Detection,” explaining that examples of “neutral” as well as “implicit” hate speech were taken from 13 minority groups, using large scale language models.

The world doesn’t know who died and made Microsoft of all companies the authority to explore the “delicate boundaries” here, but it did – the paper states point-blank, “In essence, we were using the LLM as a probe to explore the delicate boundaries between acceptable and offensive speech.”

What’s sure from the paper’s announcement is that Microsoft is not content with detecting “overtly” inappropriate language – it wants to hit harder, in more vague and open to interpretation areas.