(Psychology Today) There are a billion or so dogs on our planet, and they live in a wide array of settings—some great, some terrible. A recent study compared perceptions of the welfare of dogs in these different settings. Some of the results were surprising—particularly how people rated the well-being of their dog compared to other pet dogs.

Most dogs on earth are not treated like the typical American pet dog—a doted-on furry family member. Between 60 and 85 percent of dogs worldwide are free-ranging street/village dogs who live around humans but are not owned. While they need to scrounge around for food and rarely receive veterinary care, unlike our pampered pets, they get to call their own shots.

Then there are the dogs bred and kept for their ability to fight, hunt, or guard, and the dogs who have jobs like detecting drugs, locating human remains, visiting nursing homes, and guiding the blind. The list goes on.

The study on our perceptions of comparative canine welfare was conducted by a team of Australian anthrozoologists led by Mia Cobb, a research fellow at the University of Melbourne. Their results were published in the journal Animal Welfare. In an email, Mia told me, “The study was initially designed because I was interested in whether other people were as concerned about working dog welfare as I was. But the findings really opened my eyes and raised a whole new bundle of questions about how people think about dogs and what we believe we know.”

For Better or For Worse? Comparative Canine Welfare

The study was simple. Using social media platforms and web forums, the researchers recruited 2,147 subjects who completed a brief online survey related to canine welfare. About half of the participants were from Australia and another 25 percent were from the U.K. and the U.S. As is often the case in human-animal interaction studies, most of the subjects (81 percent) were women. (See Women Dominate Research on the Human-Animal Bond.)

In the first part of the questionnaire, the participants rated the “quality of life” of their dog on a five-point scale from “extremely low” to “extremely high.” In the second section, they rated their perceptions of 17 other types of dogs, including guard dogs, herding dogs, explosive and drug detection dogs, search and rescue dogs, service dogs, and guide dogs for the blind. The subjects also rated the welfare of street dogs, feral dogs, fighting dogs, sled-racing dogs, pedigree show dogs, and other people’s pet dogs. The subjects were also asked about the extent they agreed or disagreed with the statement, “The welfare of dogs is very important to me.”

When It Comes to Quality of Life, All Dogs Are Not Equal

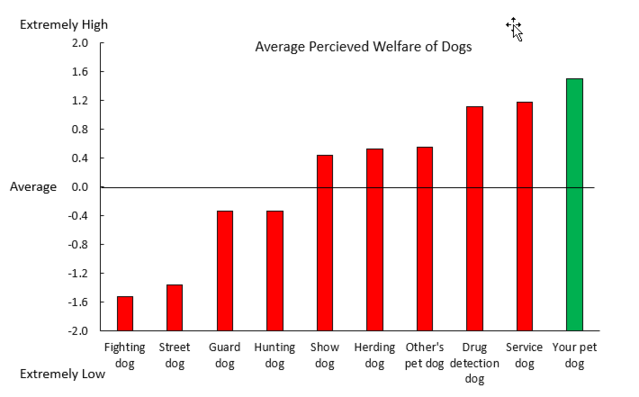

The authors found vast differences in how the subjects rated the welfare of different types of dogs. This graph shows the average perceived welfare of eight of the categories of dogs in the study.